All Best Practice is wrong but some is useful

In his book, The Future of Management, Gary Hamel tells the story of a conversation with senior auto executives in Detroit. He asked them why, after 20 years of benchmarking studies, their company had been unable to catch up to Toyota’s productivity. Here is an abridged version:

“Twenty years ago, we started sending our young people to Japan to study Toyota. They’d come back and tell us how good Toyota was, and we simply didn’t believe them… It was five years before we acknowledged that Toyota really was beating us in a bunch of critical areas.

Over the next five years, we told ourselves that Toyota’s advantages were all cultural…We were sure that American workers would never put up with these paternalistic practices.

Then, of course, Toyota started building plants in the United States, and they got the same results here they got in Japan—so our cultural excuse went out the window.

For the next five years, we focused on Toyota’s manufacturing processes. We studied their use of factory automation, their supplier relationships, just-in-time systems, everything. But despite all our benchmarking, we could never seem to get the same results in our own factories.

It’s only in the last five years that we’ve finally admitted to ourselves that Toyota’s success is based on a wholly different set of principles. It is based on ‘finding and improving small problems’.”

That anecdote speaks to many points about Best Practice; our fascination with how others do things, our search for what is superior, our human desire to copy, find short-cuts, make other people’s hindsight our foresight and most notably, the prevelance of simplicity bias.

Best Practice is descriptive, not predictive

In ‘Eat Your Greens’, Robert van Ossenbruggen speaks of the temptation to learn from somebody else’s success. “Successful individuals, brands or products must be successful for a reason – there must be a common theme, a logical explanation. Yet successes are always a minority and are partly random flukes.” Case Studies are seductive and reductive. As the Toyota anecdote highlights, determining what is causing success is tricky. There is no formula:

“No matter what anybody tells you, a formula for success does not and cannot exist. Here is why: If you’ve heard that there is a formula for success, somebody has discovered it. If one person has discovered it, surely several people have discovered it. If many people follow the same formula for success, the formula becomes the norm. If a formula becomes the norm, it cannot automatically produce hits, which are abnormally successful. If a formula for success cannot automatically produce abnormal success, then it’s not a formula” – Derek Thompson in ‘Hit Makers’

This echoes what Philip Rosenzweig, professor of strategy and international business at IMD, wrote in his book The Halo Effect: “Anyone who claims to have found laws of business physics either understands little about business, little about physics or little about both”.

Best Practice is often conflated with ‘what most people do’

Best Practice infers that there is a best way, but often it is only captured as sensible principles and tips. Best Practice often only describes the latest thinking (what proficient practitioners usually do and what typically happens) rather than leading thinking.

“Rules direct us to average behaviours. If we’re aiming to create works that are exceptional, most rules don’t apply. Average is nothing to aspire to. The goal is not to fit in. If anything, it’s to amplify the differences, what doesn’t fit, the special characteristics unique to how you see the world”– Rick Rubin.

We are drawn to comparing ourselves against averages (hence why benchmarks are so popular) and often overlook the ways in which we work that are more unique, what we take for granted. We find making sense of outliers uncomfortable because they are so far from the average. They challenge us to change our world view, which is extremely difficult. Hence, we dismiss them.

Bending and breaking the rules

The starting point should always be to deeply understand the fundamentals that support performance and achievement in any domain and to understand where to focus to influence the result. But then you have to break the rules: “Learn the rules like a pro so that you can break them like an artist” – Pablo Picasso

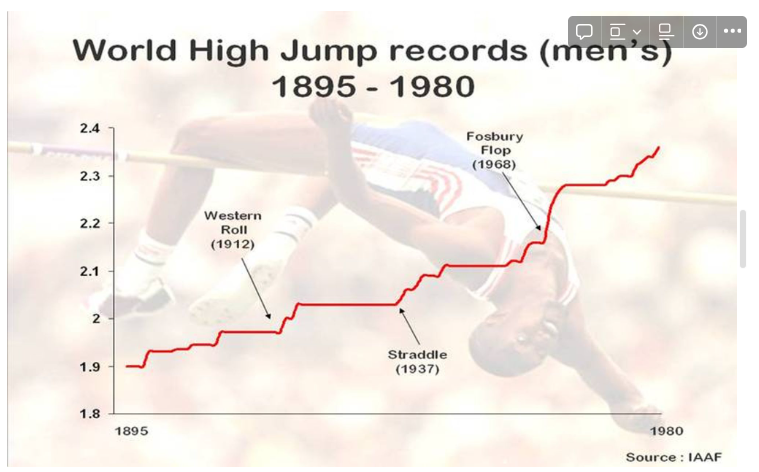

Take the High Jump, for example. The ‘Fosbury Flop’ technique changed how the sport was played.

Aristotle said that “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit”. But remaining competitive often requires disrupting ourselves, forcing ourselves to try new things in new ways without any guarantee. ‘Quality management’ practices encourage employees to eliminate the defects and waste that cause performance to vary, techniques that drive out variation and failure. But that’s a grave mistake. Variation is essential to improvement and innovation. Without Dyson’s 5127 iterations, no vacuum cleaner would have been invented on the principle of cyclonic separation. Does leading Best Practice, therefore, mean learning to tolerate failure in the short term?

Truth is outside of all patterns

When we understand the rules deeply, we move beyond proficiency and the ability to respond to situations to the fifth stage of Hubert and Dreyfus’s Model of Adult Skill Acquisition (1986), that of expert, where we write our own rules. Bruce Lee developed Jeet Kune-Do, the only non-classical style of Chinese Kung Fu.

“I have not invented a” new style,” composite, modified or otherwise that is set within distinct form as apart from “this” method or “that” method. On the contrary, I hope to free my followers from clinging to styles, patterns, or moulds. Remember that Jeet Kune Do is merely a name used, a mirror in which to see “ourselves”. – Bruce Lee

Lee believed that “Truth is outside of all patterns. Jeet Kune Do is not fixed or patterned and is a philosophy with guiding ideas. This is the central point of Best Practice. It is practised best when it is a way of thinking. “Don’t copy what people are doing; you need to copy how exponential companies are thinking” – Setting an Exponential Mindset with Mark Bonchek

Likewise, Shane Parrish talks about the dangers of blindly copying tactics:

“In American football, thousands of plays have been invented over the years, some with more success than others. Good coaches will be able to create plays based on their teams’ strengths and their opponents’ weaknesses. Their plays are based on principles that they fully understand. Play-stealers, on the other hand, spot tactics that have been effective, and plug them directly into their programs” – Shane Parrish

Common Practice is easy to find, Best Practice is much harder

In ‘The Element’, the late great Ken Robinson talked about the two quality assurance models in the restaurant business. In the Fast-food model, quality is guaranteed because it is standardised. Visit any big chain in any city, and it’s the same restaurant, the same staff uniforms, the same menu and the same tasting food. It’s guaranteed. The Michelin Guide establishes specific criteria for excellence, but it doesn’t say how restaurants should meet these criteria. Every restaurant is unique, and experts guarantee quality.

Think about the parallels to home cooking. By the mid-1950s, easy-to-prepare meals were becoming more popular, but they really took off in the 1970s as more families could afford fridges and freezers. As our lives have sped up, manufacturers jumped on the trend and started advertising time-saving meals.

Healthy, nutritious food is often three times more expensive today than fast food. But chefs like Jamie Oliver, with his ‘Recipes for under £ 1’ campaign, have repeatedly shown that higher quality, more nutritious food doesn’t have to cost the earth. But what the fast-food industry knows is that what we value most is saving time.

The choice that is better for us is often harder. We prefer easy. But the easy option now often makes things harder in the long run. It stunts our long-term growth.

Sometimes literally. A recent report has found that British five-year-olds are shorter than the five-year-old populations of our European neighbours.

But back to the business world. We can get by on quick fixes and case studies and get pulled into misleading headlines we see in the industry press, but that isn’t the Best Practice.

In summary

“All models are wrong, but some are useful” said George Box. Best Practice is rarely the best and is certainly not the only way. The alternative is ‘the beginner’s mind,’ letting go of methods, frames and recipes that stop us from creating new ways. Really taking the time to deeply think about what matters most in this context at this moment in time.

“Talent hits a target no one else can hit, while genius hits a target that no one else can see”, said the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. For target, substitute ‘Best Practice.’ Best Practice is uncommon. It requires the courage to move beyond conventional wisdom and have the courage to change the rules, and most importantly, to think differently.

Flow is a ways of working company. We help you to create the conditions where your people can flourish, where decisions, meetings and ideas can flow. If you’d like to discuss how we can help your team work with the concept of best practice to have more impact, get in touch at hi@thisisflow.co