So what if 70:20:10 doesn’t add up?

To try and drive sales of a new steps meter device before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, a company named Yamasa Tokei Keiki had to think about how to market it to a nation that didn’t know what pedometers were. How many steps per day was a good target to set? The number 10,000 was chosen because it was considered to be challenging yet achievable and, most importantly, memorable. There was another clever piece of logic. The Japanese character for “10,000” looks like a person walking; 万. It was settled; the pedometer would be called the “mango-kei,” which means “10,000 steps meter” in Japanese. As we know, it certainly caught on.

Talk about your company’s approach to learning and development, and I would be surprised if the 70:20:10 model weren’t mentioned. What’s fascinating is that the logic of that formula is about as robust as the advice to walk 10,000 steps a day. So, if the science doesn’t add up, what could be a more useful frame to think about learning?

The origin of 70/20/10

The learning and development model is often attributed to Morgan McCall, Robert Eichinger, and Michael Lombardo from the Center for Creative Leadership. The model suggests that:

70% of learning occurs through on-the-job experiences like tasks, challenges, and projects.

20% of learning comes from interactions with others, including coaching, mentoring, and feedback.

10% of learning is derived from formal training programs, workshops, courses, and seminars.

According to Wikipedia, it is based on a survey conducted in 1996 asking nearly 200 executives to self-report how they believed they learned. Michael Lombardo and Robert Eichinger expressed their rationale behind the 70:20:10 model in the following way in The Career Architect Development Planner:

“Development generally begins with a realization of current or future need and the motivation to do something about it. This might come from feedback, a mistake, watching other people’s reactions, failing or not being up to a task – in other words, from experience. The odds are that development will be about 70% from on-the-job experiences – working on tasks and problems; about 20% from feedback and working around good and bad examples of the need; and 10% from courses and reading”.

Is the proportional breakdown useful?

As George Box said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” Is 70-20-10 useful? Arguably, its greatest strength is its emphasis on experiential and practical ‘learning by doing’ and explicitly calling out the importance of coaching, which companies like Gallup and Google have found to be a major contributor to improving performance. So far, so good.

Where it becomes less useful, to the point of misleading, is in the percentages themselves and the common misinterpretation that these proportions are separate rather than deeply interconnected. Most learning is social, so why is that separate from ‘on the job’ and training, where you often learn from others?

Just think about these percentages for a moment. Who is spending 4 hours every week on formal learning (10% of a 40-hour week)? Being afforded 4 hours a month (6 days a year) is rare. From my experience working with L&D teams over the past 25 years, teams may have been approaching ten days in the 2000s but are now likely to get less than five days. That’s the equivalent of 2% of UK working days in 2024.

How about coaching? Not formal coaching from a qualified coach but good quality coaching from your people manager or an experienced team member you work alongside. Eight hours a week (20%) with your boss is a high estimate. Yes, we spend (often too much) time together in meetings, so if we assume we are learning from our peers, then suddenly 20% starts to seem low. But it blends into on-the-job experiences anyway. The figures are simply arbitrary.

Counting calories is out, it’s about the quality of your diet

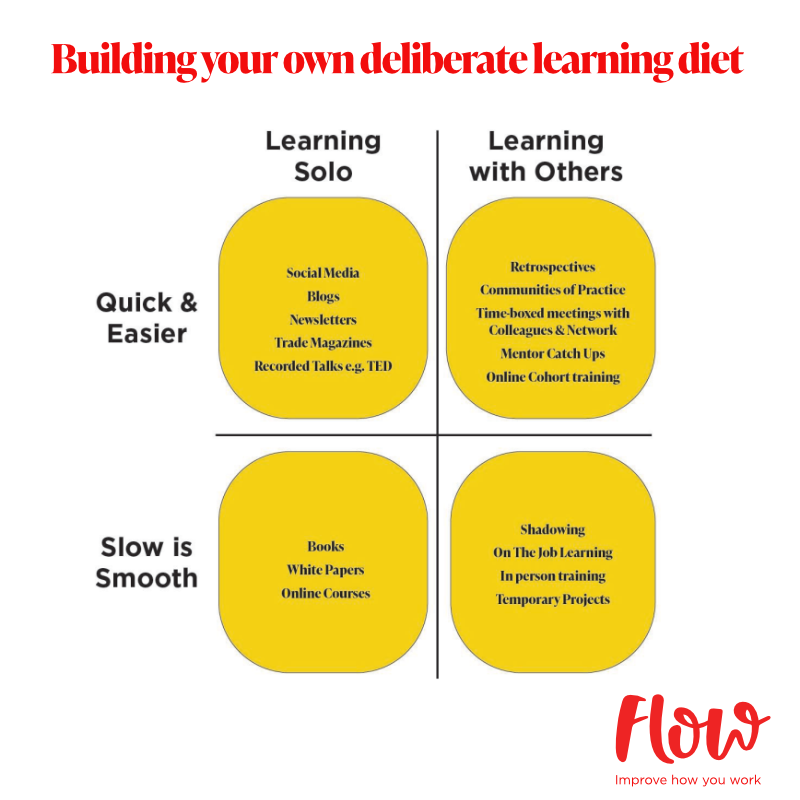

In the same way that we’ve moved beyond calories as the barometer of how to eat, a more helpful concept is to think about the quality of your learning diet. The concept of diet is stolen with pride from Faris Yakob’s lovely bit of thinking on a nutritious media diet.

You may be focused on quick snackable content that you browse by yourself. It’s tasty and convenient but not hugely satisfying and only lasts a moment. These aren’t sources that you survive on. Just ask Morgan Spurlock. Equally, nobody wants a “broccoli diet”. It looks nice and is good for you, but we need the balance.

The military has a saying: ‘Train for certainty, educate for uncertainty.’ Training is about learning and practising specific skills; education is about broadening knowledge, developing beliefs and values, and gaining experience. High-quality learning is impossible to achieve purely on your own.

‘Slow is smooth, smooth is fast’ is a Navy SEAL mantra. Deliberate and methodical are faster in the long run. A good learning diet balances convenient snackable learning with more nutritious learning. Whenever possible, tap into the collective wisdom of others. That’s because the real value of learning is about applying knowledge to your real-world context (aka the 70%).

The right learning diet can save you months and years in accelerating your personal growth.

Making time for learning

Everyone would love to spend more time learning and developing. The truth is that we are learning and developing a lot of the time (we are in the 70, 20 or the 10) but we need to be more conscious about it. We’re not deliberate about it. Making time for learning requires:

MOTIVATION to learn

Often, a lack of motivation is caused by a lack of clarity. What knowledge, skills and behaviours do you need to isolate and improve to accelerate your development and impact? Why is isolating knowledge, skills and behaviours (KSBs) important? Because “most development revolves around one huge false assumption: If people understand, then they will do. That’s not true. Most of us understand, we just don’t do.” -Marshall Goldsmith.

We need to figure out what’s most helpful to read and watch and who to listen to. Skill is always gained in the context of practice and behaviour is influenced by what we value, what we believe and what motivates us.

You need to focus on the part of your game that determines the result. What is it that the best are doing differently? They may be working with a different process, but it’s more likely to be better techniques or more helpful behaviours. These are what you need to isolate. What exactly does success look like in your role, where do you see the opportunity to improve and specifically, what should you be doing instead? If you can answer these three questions, you can set up a feedback loop to challenge yourself and learn from.

INSPIRATION to learn

The word inspiration comes from the Latin ~ inspirare, meaning to breathe in or blow into. If we are what we consume, we need a learning diet that is nutritious. We’ve covered how to do that above.

PRIORITISATION for learning

When I ask or research why people don’t spend more time in the learning zone, I hear these two justifications more than any others:

I’d love to spend more time learning, but I don’t have time

My company doesn’t provide us with training opportunities

I think that busyness, combined with “learning isn’t valued by leaders,” is at the top of the list of reasons people deprioritise learning. When in Rome, we tend to do what other Romans do. Task completion comes first, second and third. The problem is not having too little time to do what we have to do. It’s that we give ourselves too much to do. Unless you first place the big rocks into the jar (your family, your friends, your personal growth), you’ll spend all your time doing the work.

When we justify, we tell ourselves stories about our circumstances. We feel powerless in the situation. We develop our own agency by rejecting the story and committing to learning and investing in our personal growth. It’s up to all of us to choose where we invest our time and what commitments are non-negotiable.

CONSOLIDATING our learning

It would be lovely if our brains worked like hard drives where we could easily store and retrieve information. But the brain acts more like a web of patterns than a hard drive. When we practice things over and over again, our brain activates subroutines. The more we practice, the easier it is for our brains to retrieve these patterns. Do this enough, and we become experts. But knowledge is entirely different to skill. When we passively consume it, it doesn’t create patterns in our brains. We hear and watch valuable insights daily, but they evaporate into thin air. The modern workplace’s constant email flows and back-to-back meetings make reflecting hard. Reflection feels like the antithesis of being busy. We have unconsciously fallen into insight-preventing ways of working.

Without reflection, there is no learning.

Instead, you can accelerate your development and learning simply by creating the routine of capturing and consolidating your learnings by reflecting periodically on what you’ve experienced, what works, what doesn’t, what you’ve learned and how you might do things differently.

That’s a great practice both on your own and with your team. Retrieving what you previously wrote down makes you a memory master. Start a learning notebook, and it will be the gift that keeps giving.

In summary

It comes down to a question of emphasis:

So what if 70:20:10 doesn’t add up? The model may not be based on scientific data but its strength is in underlining that ‘learning by doing’ is the biggest source of learning and that learning is always a blend.

So what if 70:20:10 doesn’t add up? The model is misleading because it artificially separates learning into distinct categories which aren’t mutually exclusive. What’s important to remember is how important social learning is to how we learn. We’re typically learning from others when we work and most work is done in some collaborative setting.

Deliberate learning plans should acknowledge that accelerated learning comes from working alongside other people, that creating deliberate learning moments in work need to be prioritised if reflection and learning are actually to happen. Because we don’t actually learn by doing. We learn by reflecting on what we have done.

Flow is a ways of working company. We help you to create the conditions where your people can flourish, where decisions, meetings and ideas can flow. If you’d like to discuss how we can help your team create a stronger learning environment that supports growth, get in touch at hi@thisisflow.co