How to involve the right people. Not too many, not too few

There’s a particular kind of meeting that most people have sat in at least once. It’s the one where you look around and quietly wonder: does everyone here actually need to be here? The answer is usually no.

Collaboration suffers at both extremes. Involve too few people and you miss the expertise, perspectives, or buy-in that make good decisions. Involve too many and you create a coordination burden, dilute accountability, and burn people out. Many teams have learned to fear the first failure but haven’t reckoned with the cost of the second.

Getting this right is genuinely hard. It requires judgment about people, context, and stakes. But it’s also a skill that can be developed and the starting point is understanding why we need other people’s opinions but often ask for too many.

Why the usual suspects aren’t enough

Shane Snow’s research in Dream Teams offers a striking image: imagine a mountain range where each peak represents a possible solution to a problem. When you explore that mountain range with a group of people who all started from the same base camp, you’ll eventually find a good peak and settle there together. The trouble is, you may never discover there’s a higher mountain on the other side of the ridge.

Dr. Scott Page’s research, which Snow draws on extensively, is unambiguous: teams with diverse mental tool kits, different ways of seeing problems and different heuristics for solving them, consistently outperform groups of the best and brightest who think similarly. Not because diversity is inherently good, but because novel problems, by their nature, require angles that no single perspective can provide.

The psychologists call what happens to familiar, comfortable teams ‘cognitive entrenchment.’ The longer people work together, the more their thinking converges. Best practices become defaults. Defaults become invisible. What worked before becomes the only thing people can see. Snow notes that this isn’t a character flaw but a feature of how expertise works. The better you are at something, the harder it becomes to imagine doing it differently.

This isn’t an argument for making every team larger and more diverse. It’s an argument for being more intentional about the gaps you’re trying to fill when you decide who to bring in.

The collaboration tax you are charging to others

Here’s what often gets missed in conversations about inclusion: every person you bring into a project or decision carries a cost for them. Their attention is finite. Their workload is already full. Being consulted, asked for input, or dragged into a meeting they didn’t need to be in is a subtraction from their capacity to do their own best work.

Susan Finerty, writing about cross-functional influence, puts it well: the most effective collaborators make it structurally easy for partners to support them. That means being specific about what you need, giving advance notice, making the ask appropriately sized, and critically, respecting when someone says they’re stretched. The reflex to involve everyone ‘just in case’ is often less about the work and more about protecting yourself from being wrong.

Your company’s collaboration overload; too many meetings, too many threads, too many requests, is partly the aggregate of hundreds of individual decisions to involve one more person. At the structural level, this is what Flow’s research identifies as ‘invisible demands’: collaboration that is unmeasured, and therefore unmanaged. But the structural problem is made up of individual habits. And one of the most common individual habits is the instinct to over-include.

The accountability trap: why over-involvement is often structural

There is also a subtler cost that rarely gets named; when too many people are involved in a decision, individual accountability becomes diffuse. When accountability is diffuse, the rational response for each person is to protect themselves by widening the consultation further. You involve more people not because their input will improve the decision, but because being seen to have involved them reduces your personal exposure if things go wrong.

This compounds when companies fail to distinguish between accountability for an outcome and for the inputs into the decisions that shape it. You are rewarding the appearance of participatory decision-making over the quality and speed of actual decisions.

Four questions to know if you’re involving the right colleagues

The Goldilocks test is about which people to include, and why. To deliver better outcomes without overwhelm. A useful check before involving anyone in a project or decision is to work through four questions:

1. What perspective do I genuinely lack? Think about the mental models you’re bringing to this problem. What assumptions are embedded in how you’ve framed it? Who in your company sees the world differently enough, through a different function, a different geography, to challenge those assumptions? What is the specific knowledge, perspective, or capability that this person brings that nobody already involved has?

2. Are you involving them to improve the work or to protect yourself? This is the uncomfortable question. Some collaboration is genuinely about making better decisions. Some is about distributing accountability, creating cover, or avoiding the discomfort of being wrong alone.

3. Do they have the capacity to actually engage? This is the question that most people skip. Involving someone who is already at capacity doesn’t give you their best thinking.Before you add someone to a meeting, a document review, or a decision, ask yourself: do you actually know how loaded they are right now? If not, check. If they’re stretched, consider whether you need their input now or could time it differently. Don’t guilt-trip. Adjust.

4. What do they need to contribute, and what will they need from me? Reviewing a document, creating slides, and leading a workstream require different levels of involvement and different types of commitment from both sides. Someone whose perspective you need for one short conversation is not the same as someone who needs to be a co-owner of the work. Being clear about which role you’re asking someone to play and how much of their time and attention that actually requires prevents both over-involvement and under-preparation. ‘Can I get your perspective on one aspect of this?’ is a fundamentally different ask to ‘I’d like you to be part of this decision.’

The three groups

A simple framework for structuring who belongs where is to think of 3 groups.

The core circle contains the people with direct accountability for the outcome, and those whose specific expertise is central to the work from the start. Keep this circle small and deliberate. Every addition increases coordination cost.

The consultation circle contains the people whose input you need at defined points, but who do not need to carry the work end-to-end. They might review a draft, challenge a key assumption, or flag a downstream implication. Their involvement is episodic rather than continuous (and I’ll talk about this in the next section on being considerate).

The informed circle contains the people who need to know about the work but do not need to shape it. Keeping them informed is a courtesy and a communication task, not a collaboration task. Conflating these two things is how the core circle inflates.

Input quality that’s considerate

Even with a carefully selected group, there is still the problem of getting genuinely useful input rather than polite and superficial responses. A common failure mode is involving the right people and then briefing them so badly that you get surface-level replies rather than real thinking.

The first request failure is vagueness: ‘I’d love your thoughts on this.’ The second is over-briefing; a wall of context that makes it unclear what you actually need.

A three-part structure can help.

Part 1: Context in one sentence

Situation, question or decision, and how far along you are. The last element is the one most people skip — and it is arguably the most important. There is a significant difference between ‘I’m still figuring this out’ and ‘I’ve committed to a direction and I’m stress-testing it.’ When you are honest about your openness, you enable the other person to calibrate their response correctly.

Part 2: Why you specifically

Not ‘I respect your perspective’ — everyone says that. What is the specific lens you are asking this person to apply? What do they see that you don’t? Being precise here activates the right mental model before they start thinking. It also signals that you have done the work of understanding what you need, which tends to produce more generous and focused responses.

Part 3: A focused question with an open door

Lead with the specific thing you are most uncertain about. This respects their time and focuses their energy where it matters most. Then follow with a genuine invitation: if they see something you haven’t framed as a question, you want to hear it. The sequencing matters; the focused question first makes the open door feel real rather than performative. If you begin with ‘what do you think?’ and then add a specific question, the invitation feels like an afterthought. If you begin with the specific question and then open the door, you’re saying: here’s what I need, and I mean it if you’ve spotted something I’ve missed.

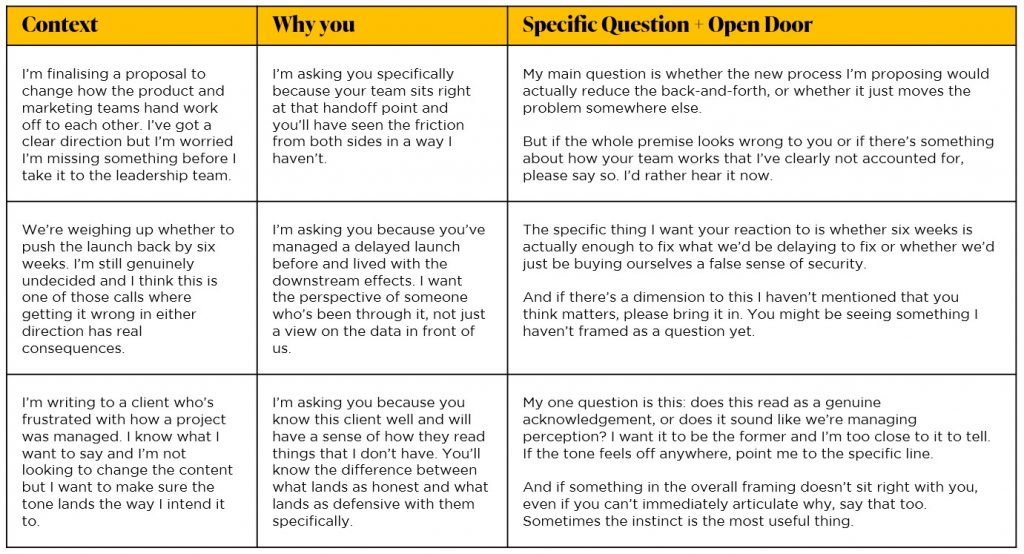

Here are three worked examples, each in a different context:

The briefing structure as a readiness test

Notice that all three examples are short. None would take more than 30 seconds to read. That brevity is deliberate. The discipline of the three-part structure forces you to have done your own thinking before you involve someone else.

A great deal of collaboration overhead is created not by involving too many people but by involving people too early before the question is clear enough to get useful input. The briefing structure is a readiness test as much as it is a communication tool.

The calibration skill

None of this is simple to get right in practice. Companies create pressure to over-include through politics, through a desire to be seen as collaborative, through genuine uncertainty about who needs to be in the room. Resisting that pressure requires both good judgment and a degree of confidence that the judgment will be supported.

Being kept informed is not the same as being consulted. Making these distinctions clearly and consistently is a form of respect for people’s time and attention that most workplaces would benefit from more of.

In Summary

Consult the voices most likely to challenge your blindspots. Respect everyone’s capacity. Be honest about which circle each person belongs in and why.

That’s not under-collaboration. It’s not over-collaboration. It’s just right.

Flow helps organisations identify and remove the structural barriers that make collaboration harder than it needs to be. Contact hi@thisisflow.co if you have a challenge you’d like to explore.