Enabling Cultures: What Matters More Than AI for Team Potential

This week, I realised I’ve spent 30 years working in and with teams. In that time, technology has changed the way work feels. My first job was with one team in one office, all together. Now, I’m part of several teams spread out across locations, often working at different times but always staying connected.

As AI transforms how we’ll work, the question isn’t just how this technology will help. It’s whether we’ll finally address the organisational barriers that hold teams back from reaching their potential.

How did we get here? What does teamwork feel like today, and what happens next? I sat down to reflect and make sense of my career working in teams.

THE CHRONOLOGICAL JOURNEY

1995-2010: The Digital Foundation

1. Email becomes mainstream. When I started my first job, colleagues were hand-writing memos and using typing pools. But by the late 90s, email had firmly become established. Broadband replaced dial-up modems. BlackBerry devices in the early 2000s and wireless internet promised to eliminate communication delays and fundamentally changed the quantity of communication at work.

2. Version Control chaos. By the early 2000s, Microsoft’s Office Suite were essentially synonymous with office work. We were emailing Word docs and Excel spreadsheets back and forth, with “Budget_Final_v3_REVISED_John’s_edits_FINAL2.xlsx” sitting in everyone’s inbox. Teams used shared drives with hard-to-follow folders. SharePoint and early collaboration platforms became graveyards of unfindable documents. Intranet pages rarely got updated. Early instant messaging let us see if co-workers were available or busy.

3. We were rapidly gaining flexibility but losing boundaries. With powerful computers in our pockets, smartphones sold as flexibility actually delivered permanent availability. Welcome to being ‘always-on’.

4. A new era of global work began. Before email, working across countries meant costly phone calls, faxes, and lots of travel. By the late 2000s, global teamwork was normal in big companies, pushed by cost, supply chains, and competition.

- Global category teams were standard – the person leading Dental Care in GlaxoSmithKline in Brentford worked daily with colleagues in Geneva, Singapore, and São Paulo.

- We saw massive offshoring and the creation of Global Business Services centres.

- Centres of Excellence emerged to drive innovation across core global markets.

- Matrix structures proliferated with promises of improved collaboration, but mainly delivered competing priorities, multiple bosses, and exhausting political navigation.

5. Coordination started to explode. The ease of digital communication paradoxically fuelled our reliance on meeting culture, sometimes meetings just to talk about emails or plan other meetings. Coordination (e.g. status updates, effort alignment, syncing schedules, managing handoffs, waiting for each other’s input ) was getting in the way of real collaboration (joint problem-solving, planning and implementation).

Pretty soon, almost everything we were doing at work required collaboration: answering emails, instant messaging, meetings, and using other team collaboration tools and spaces. We were spending increasing amounts of time determining the status and progress of work, chasing tasks and following up with colleagues in other teams (by 2023, coordination was taking up 58% of the workday, with skilled work taking up 33% and strategic work just 9%. Source: Asana Anatomy of Work).

2010-2020: The Acceleration

6. Calendar tyranny was growing. Technology lets us work together across distances and time zones. But global teams found that ‘follow the sun’ often meant meetings at inconvenient times for someone. Back-to-back meetings from 8 am to 6 pm left us finishing tasks in the evenings.

7. Team membership became fluid and simultaneous: people found themselves on five tor six teams at once as cross-functional work became the norm.

8. It’s VUCA time. The term, coined by the U.S. Army War College in the late 1980s/early 1990s to describe the post-Cold War world, began to enter business vocabulary. Standing for volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, leaders began adopting the phrase to describe the impact of rapid technological change, globalisation, market disruptions from startups, and shortened product lifecycles. Change was framed as our new constant. Klaus Schwab, the WEF’s founder, introduced the term ‘The Fourth Industrial Revolution’ in 2016 to describe the advancements that bring unprecedented challenges.

9. Microsoft’s collaboration tools became good rather than just unavoidable. Cloud computing was accelerating location-independent work and enabling asynchronous collaboration at scale. Office 365 launched in 2011, but it wasn’t until much later in the decade, with the launch of Teams in 2017 and the modern SharePoint experience, that we began to glimpse the potential of collaboration platforms. High-definition video calls had become free and ubiquitous. The teleconference line was dead.

10. We began to miss real connection. More collaboration tools didn’t mean we felt more connected. We were always communicating, but genuine relationships were fading. By the end of the decade, fewer hybrid workers said they had a best friend at work. This is important because Gallup’s research shows that having a best friend at work makes people seven times more likely to be engaged, and these friendships help with retention and performance.

2020-2025: The Reckoning

11. The pandemic made everyone work remotely almost overnight. Office-based routines disappeared, showing what was possible when strict 9-to-5 schedules were replaced by flexible autonomy.

12. Is commuting really worth it? Colleagues weren’t missing the dead time spent travelling to and from work and were questioning the real benefits of in-person work. Amazon’s Andy Jassy had solicited 60 to 80 CEOs of other companies, and this echo chamber concurred that they all preferred in-office work. These executives consistently emphasise:

- Innovation suffers. Serendipitous water-cooler conversations happen less frequently when remote.

- Mentorship and coaching break down. First-job colleagues learn more slowly without in-person role modelling.

- Culture weakens. It’s harder to strengthen and transmit company culture virtually.

- Productivity declines (although there is no indisputable evidence).

Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon called remote work an aberration, and Dell, Apple, Google, IBM, Salesforce, and Microsoft are among the companies that have implemented strict RTO mandates requiring three to five days.

13. Questions of flexibility. After the pandemic, people want not just location flexibility but also more control over when they work. For many, the pandemic was a turning point to rethink priorities, work-life balance, and career goals. Of course, this looks different depending on your life stage and whether you work in an office, factory, or service job.

14. Will AI help turn around declining productivity? Productivity gains (output per worker) have decelerated across developed economies since the 1970s, and many are seeing their working-age populations shrink. So is AI going to deliver? Will AI and automation finally boost productivity enough to offset demographic headwinds? Most of the specific, quantified internal data that select companies have shared comes from pilot programmes or specific use cases rather than company-wide transformations. The harder data tends to focus on time saved on specific tasks (meetings, emails, coding) at the individual and team levels rather than on overall business outcomes at the organisational level. How long before AI is delivering better quality as well as greater speed?

But there is one hugely significant implication of greater speed: the collapse of the billable hour, which has been the lifeblood of large consulting firms. When I left big consulting in 2022, the billable hour determined who we could assign to different projects and how much of their time we could afford. Finally, these companies have no choice but to move to outcome-based pricing. This is a huge win for clients.

15. If culture is ‘how we work around here,’ it’s all being redefined. As Julia Hobsbawm says, “It turns out that the definition of what productive work is and how work culture can be successfully fostered needs to be radically revised… it’s the beginning of a new time in which place, identity, culture, purpose, wellbeing and productivity occur against a new set of working conditions” (source: Working Assumptions)

ADDRESSING THE CONSTRAINTS OF TEAMWORK AT SOURCE

Culture is the way we work. It’s how we deliver performance. Culture is how we create the conditions that enable people to do great work together.

Richard Hackman said in the 2000s that teams didn’t always reach their collaborative potential because coordination challenges were getting in the way; “Research consistently shows that teams underperform, despite all the extra resources they have. That’s because problems with coordination and motivation typically chip away at the benefits of collaboration.”

After all the changes in the past 30 years, it seems that coordination challenges are now a bigger obstacle to real collaboration and teamwork than ever before.

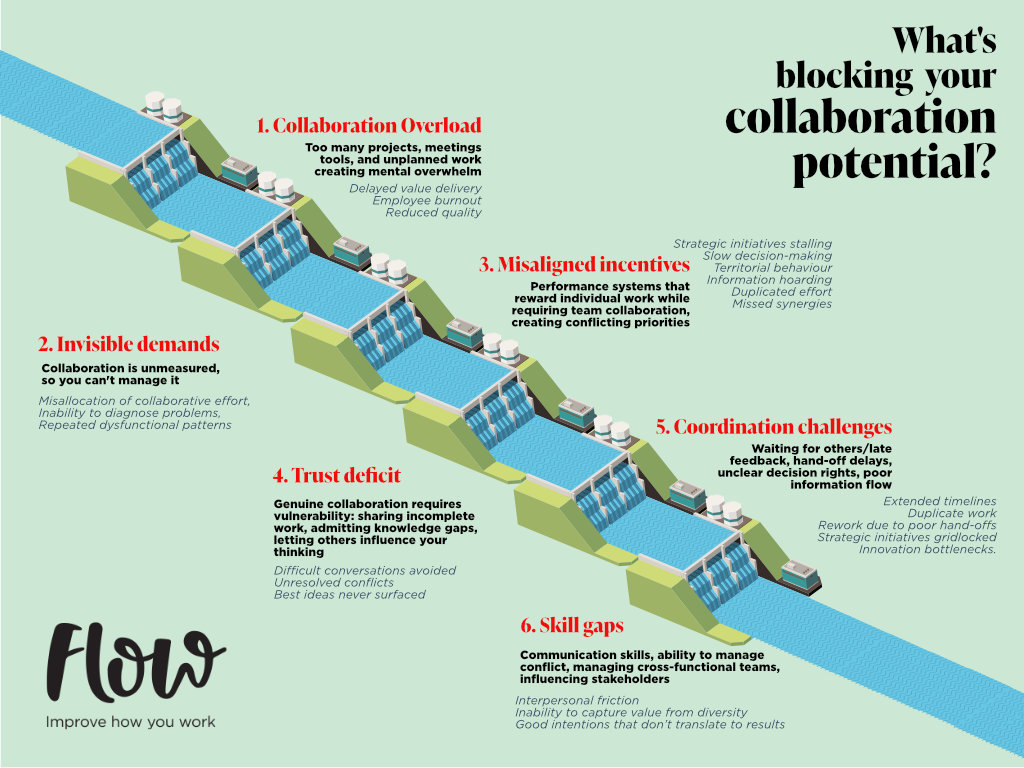

What is holding teams back from being the engine of future value? How do we help individuals and teams play to their true potential? I believe there are several factors:

16. We’re seriously overloaded. Between 1980 and 2000, Americans added 164 extra work hours each year. Early in the pandemic, people worked 22 million extra hours every workday (Both sources: Out of Office). We’re still stuck in too many meetings. Burnout, first named in the 1970s, was recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2019 as a workplace issue. It’s defined as a syndrome from ongoing work stress that isn’t managed, with three signs: lower effectiveness, feeling drained, and feeling distant from your job.

When it comes to energy, 80% of workers and leaders worldwide say they don’t have enough time or energy to do their jobs (source: The Year of the Frontier Firm is born). Microsoft’s latest Work Trend Index shows just how much nonstop communication and meetings have pushed people past their limits.

Our new goal should be to work less but work better. What other choice do we have?

17. Collaboration demands are invisible. You might have tried explaining your job at a party, only to see someone’s eyes glaze over. We all have a rough idea of what our coworkers do, but we don’t really know who they work with or what requests they handle. No one has a clear view of how work moves between teams. What does good collaboration look like, and when does it happen? It’s all left to individuals to figure out.

Collaborative work is unmeasured, unseen, and poorly understood.

18. Misaligned Incentives & competing priorities. Incentive systems remain misaligned with teamwork. Performance management rewarded individual contributions, and collaboration credit became diffused. We’ve designed organisations that:

- Maximise individual accountability (so we know who to promote/fire)

- Optimise for measurable output (so we can “manage performance”)

- Create competitive internal markets (so people stay motivated)

- Reward visible leadership (so we can identify “talent”)

All of these made sense in a world of simpler, more modular work. But they make collaboration structurally expensive and less rewarding for individuals.

The sad part is we blame people for ‘not being collaborative enough’ or ‘working in silos,’ but they’re just reacting to how the system is set up.

As companies have become more matrixed and project-based, when different teams are competing for shared resources, priorities and trade-offs become battlegrounds for individual team survival. When people feel threatened, the effect of in-group identification becomes more intense.

Teams are suffering from the absence of coherent direction and a sense of achieving together. How teams need to join together is the missing link.

19. Trust deficit. Collaboration requires vulnerability; sharing incomplete work, admitting knowledge gaps, letting others influence your thinking, sharing credit and accountability. But when companies punish vulnerability through blame cultures or weaponise mistakes, collaboration inherently creates professional risk. Team diversity is good for business, but it can take significant effort to realise these benefits:

“When team members come from different cultures, are of different ages, unequally fluent in the team’s working language, or differ otherwise at the personal level, they tend to find it less enjoyable to spend time together, trust each other less, make less favourable attributions about each other’s motives, and generally communicate less. As a result, they experience less cohesion and have more conflicts and misunderstandings”(source)

20. Coordination mechanics & dependencies. The greater the number of teams, the greater the work in progress, the greater the coordination headaches. Tasks spend more time in wait states than work states. We can’t schedule meetings soon enough because key colleagues are tied up in other projects.

21. Capability & Skill Gaps – It’s hugely common to see underdeveloped skills in being able to communicate clearly with colleagues, make decisions together and manage conflict productively. These three skills alone undermine our ability to achieve genuinely important things together. The benefit of collaborating is about harnessing differences. Divergent views often lead towards a more profound understanding of the problem, but we’re becoming less tolerant of truly listening and empathising. If we can’t understand each other, if we aren’t willing to be open-minded, if we can’t quickly fight and unite around positions that unite us, then the value of teamwork is diminished.

True teams have a shared mindset, a compelling joint mission, defined roles, stable membership, high interdependence, and clear norms. But as I’ve already spoken about, we’re increasingly working on projects where colleagues come in and out. We’re working in groups but expecting the output of teams.

We need to figure out how to reach high performance faster.

22. In short, we say we value collaboration, but our systems don’t support it. Performance systems, recognition structures, and career progression all reward individual heroics over teamwork. We add Slack channels and ‘collaboration tools’ without removing the individual incentives. We talk about psychological safety but don’t tolerate missed targets.

We apply pressure to individuals by reinforcing ownership and accountability whilst taking limited enterprise accountability for protecting employees from overload, the true extent of which is not diagnosed, understood or mitigated.

THE NEXT CHAPTER – GROWTH THROUGH MORE ENABLING CULTURES

23. How teams work matters more than who is on them. That was the key conclusion from Google Aristotle in 2012. Around the same time, MIT’s Human Dynamics Laboratory concluded that patterns of communication explained performance more than individual talent.

24. Investing in teams drives growth. Prioritising employee performance impacts revenue (McKinsey, 2024), and improving teamwork requires structural change, not just skills training. A helpful case study here is Microsoft, which embedded ‘Manager Expectations and Principles’ as a priority in their performance management system, i.e. making it structurally necessary rather than merely encouraged.

25. We’ve known for decades what people want from work. Management expert Jeffrey Pfeffer wrote ‘The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First’ almost 30 years ago. His research amongst successful companies, on what creates ‘high commitment workers,’ includes all of the usual suspects:

- Employment security and remuneration in line with the market

- The company’s mission is lived and breathed outside of town-hall speeches

- Giving employees autonomy through self-managed teams and decentralised decision-making.

- Development opportunities, including ongoing training

- Not over-measuring employee performance

That’s a solid starting list. Over the past 30 years, we’ve introduced a slightly different set of terms. Remuneration has been broadened to recognition and being seen for contributions, not just output. Mission has been superseded by the ideology of wanting to be part of a bigger purpose. Connection and Belonging at work have become more critical as our societal structures have weakened (including communities, ironically, because we are spending so much time and energy at work).

But let’s address the big issue. A recent piece of research by Fauna, their Work Possible Report 2024, identified six consistent elements people want in their best workday. They’ve all largely been covered above, with one exception:

Balanced Headspace – time and mental space to do great work without burnout.

26. Redesigning workflows to work less with better results. In 1911, Frederick Taylor formally published The Principles of Scientific Management and popularised the framework that would fundamentally reshape how factories organised human labour alongside machines. Taylor’s work was about intensifying work within whatever hours were worked; making every motion count, eliminating waste, and maximising output per hour. Fifteen years later, Henry Ford implemented the 40-hour work week at the Ford Motor Company after finding that shorter hours increased productivity.

The hard work of the next 24 months is figuring out how AI can rewire how work gets done in companies. AI’s superpower is coordination, the meta-blocker that prevents us from spending more time on strategic and higher-value tasks. Currently, it’s impossible to see the whole picture given how we have sliced and diced priorities, strategies, and tasks across our companies. AI will get better at coordinating across multiple systems, functions, and geographies to take away the pain of scheduling, status updates, information synthesis, and task routing. Technology will enable collaboration in much larger and more diverse groups than ever possible.

27. Human-AI Partnership. People will need to learn how to work alongside AI agents, teach AI agents new skills, and design new uses for technology. Individual contributors will become team leaders managing autonomous agents and robots. Thomas Malone believes that workplace collaboration will fundamentally reorganise around three elements:

- Dividing work in new ways (hyperspecialization)

- Assigning tasks in new ways (self-selection and automated matching)

- Coordinating interdependencies in new ways (cyber-human systems)

Learning quickly and continuously, and being able to adapt to rapidly changing work environments, is what we have been doing for the past 30 years, but the acceleration will be greater.

28. Skills that we’ll need to develop to work effectively with AI. Azeem Azhar identifies three critical skills:

Abstraction – the ability to step back from the specific details and see the bigger picture or underlying structure. Operating at the level of what you want to achieve and why, not the nitty-gritty of how. Senior developers naturally think architecturally; they’ve learned to mentally map out how different components fit together before touching the keyboard. When working with AI, this means clearly articulating the intent and structure of what you need, not just the implementation details. As workers, we haven’t always been great at goal setting, and arguably, this needs to change.

Clarity – precision in communication, the ability to specify precisely what you want without ambiguity. It’s the difference between telling AI “make this better” and giving much more nuanced, directional instructions. Having spent most of my career in marketing and marketing training, I can confidently say that clear briefing isn’t straightforward. Being able to articulate requirements clearly and unambiguously is precisely what makes AI produce useful output on the first try rather than needing endless iterations.

Evaluation – critical judgment. Knowing whether what comes back is actually good, safe, and fit for purpose. How to monitor AI performance and judge quality.

29. Doubling down on our human differentiator. If we are to finally reduce the time we spend on menial tasks and reclaim our energy, how will we spend it? On defining and working with cyber-human teams to solve complex problems? Bringing contextual understanding, our creativity, and our social and emotional intelligence? These are the skills that AI lacks. Malone hypothesises that platforms will facilitate matching specific skills to specific tasks globally. We may need to become hyper-specialists in chosen skills.

Final Thought

30.My summary reflection after 30 years? Not that collaboration has gotten worse or better, but that we’ve been solving the wrong problem when it comes to better teamwork. We’ve been adding tools instead of removing barriers. AI will help solve the coordination burden that has limited team value creation, but it is only one of the six barriers blocking collaboration potential. As long as humans are part of teams, there is an opportunity to remove the other barriers that slow progress